K: I knew you’d make it! I’ll start. What have you been working on for the exhibition?

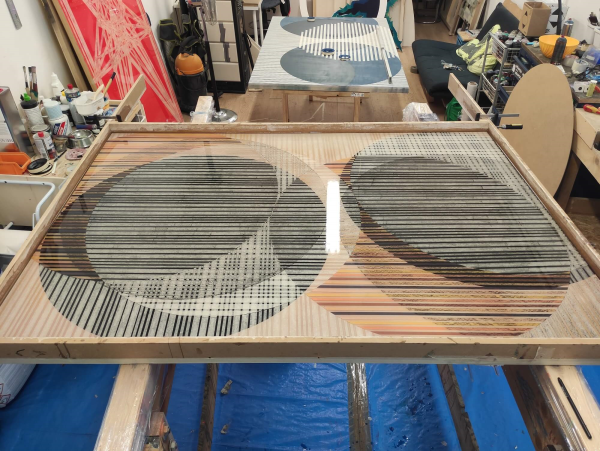

E: I’m working on a series of new artworks; I’ll title it “Manifesti satellite”. I have studied how to organize the composition for a long time, first on paper and then digitally, through Illustrator. It will be three couples of circles that overlap following the same structural scheme on two layers of resin. I wanted to standardize the composition to work more carefree with new colours and materials.

Although they share the same compositional logic, the paintings will differ greatly. I am also trying to include those “disruption moments” we spoke about last week. I like this direct exchange of images we are having; it’s like you could see my paintings before they are even finished and vice-versa.

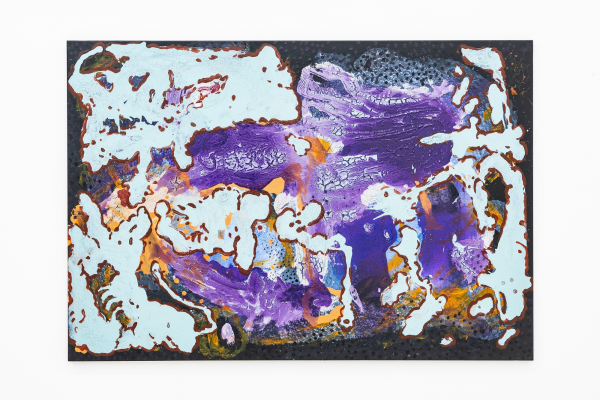

K: Surely, one of the aspects our works share is the concept of wait. The actions on our artworks are often fast, but the drying process is extremely lengthy. This allows us, or rather forces us, to sit and watch for a long time. I am working on a new group of artworks, too. They are all based on the same starting point: to try and reproduce the purple-blue base of this work.

Although I know exactly how it was done, I haven’t succeeded in the endeavour yet. There are many variables to consider besides the materials, and, unfortunately, I cannot recreate them nor control them. Then, there is another factor; since I work on layers, I almost always find myself trying to bring something new or exciting out of the canvas, yet I don’t want to force the artwork to take a different direction from the one it chose. So it will already be a miracle if I succeed in presenting one painting with a purple-blue base!

Although I know exactly how it was done, I haven’t succeeded in the endeavour yet. There are many variables to consider besides the materials, and, unfortunately, I cannot recreate them nor control them. Then, there is another factor; since I work on layers, I almost always find myself trying to bring something new or exciting out of the canvas, yet I don’t want to force the artwork to take a different direction from the one it chose. So it will already be a miracle if I succeed in presenting one painting with a purple-blue base!

E: The drying time always seems eternal. We both wait for the artworks to dry horizontally, and looking at the paintings while lying down is always an alienating experience. Maybe this is why my pictures do not have a specific orientation; when I create them, I fly over them from right to left, from the bottom up, and vice-versa.

These aerial visions extend the observation times because of their perspective: it is as if you were looking down from an airplane window; you are going very fast, but your gaze and time are slowed down. To be able to slow something down is always very fulfilling, especially nowadays.

These aerial visions extend the observation times because of their perspective: it is as if you were looking down from an airplane window; you are going very fast, but your gaze and time are slowed down. To be able to slow something down is always very fulfilling, especially nowadays.

K: Working like this amuses me, considering I have always been highly impatient; it is as if I was willingly obstructing my impetus. I often find myself revolutionizing an artwork just because it hasn’t dried yet. I like to bring myself to that level of impatience where I overturn the whole situation just to get back to work, throwing even more material on the artwork. And everything changes again.

E: I was thinking about the first time we talked about organizing a show together… I was washing the dishes at your place after eating spaghetti with tuna and thought about how people only wash dishes when they are at home or at someone’s they spent the night with…There is a quote from Kippenberger: “simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful. The whole network is important! Even spaghetti. When you say art, then everything possible belongs to it. In a gallery that is also the floor, the architecture, the color of the walls”. I like to think that that spaghetti dish contributed to the expansion of our network to the point we now work together. Of course, the exhibition is always the final result we present to the public, but in this case, I feel like we are not worrying too much about the end of the process; we are just sharing our network to create art.

K: I am under the impression that you, too, tend to draw from sources foreign to what is considered “painting”. For instance, my best inspirations come from cooking or being seated at the dinner table. In fact, Pando comes from a dinner conversation about trees in which I came across this creature, a millenary colony of trees. This means that there are both young and older trees, yet they are substantially clones; it is as if they were the same tree. As if they were a giant’s hair. I like Pando because it is the same feeling I experience when I am in my own studio: I have fresh works and others from more than ten years ago lying around; they are all mine, yet they are at different stages.

E: You hit the nail on the head! The pando is the heaviest organism in the world and the second largest. We see thousands of trees, but, in reality, they are one single being made of root connections or networks. The images of Kippenberger’s spaghetti and pando are very similar if we analyze them through the lens of us working together. A spontaneous unification or regrouping that is not aimed at a specific objective but at the pleasure of painting and creating a network of exchanges, not just contacts.

K: It’s been a while since the last time we wrote to each other, and I think it would be interesting to analyse what has happened to our artworks in the meantime. I, for instance, after multiple attempts to recreate that galactic blue background, created far darker ones, almost black, adding sesame seeds to the mixture. The bases are opaque, but through the later steps that are often transparent and glossy, the reliefs created by the sesame “light up”, recreating a sort of starry sky. And the following steps emerge from the darkness.

E: I finished the small and big-sized works. I’d like to create two more pieces of medium size. I succeeded in following the composition I designed at the beginning. From a scientific point of view, my attitude towards painting has always been very conservative, but this time it was more oriented toward the concept of “de-extinction”. I’ll make myself clearer. In the last few years, science has been developing “de-extinction” techniques such as cloning and “breeding back” to solve the problem of species extinction. Let’s take, for instance, the quagga, an African zebra that has been extinct for 40 years. Scientists have tried to replicate it through an artificial selection that would create an animal with a phenotype similar to the extinct specimen, although without recovering the original genetic material. So now there are zebras in Africa nearly identical to the quagga, but they are not really quaggas. I think this slight change of course in my works has happened thanks to the strict contact with you and your artistic practice. Probably, only a trained eye would be able to notice this development in my work, just as a few people might spot the difference between a real quagga and a cloned one.

K: Probably, one might need much time to notice these changes; with this, I don’t mean spending time in front of the artworks at the exhibition. On the contrary, I think about analysing the painting over a long time, by having it in one’s studio, home, or their workplace. It is a very different analytical process, made of fragmented looks, often less demanding, and free of the need for understanding.

E: I’d like to go back to the sesame seeds and starry skies. I am under the impression that you’re trying to achieve greater seriality through this group of artworks. Isn’t it so?

K: I don’t know if using the term “seriality” is appropriate; maybe it is more about analogous starting points. Let’s say there is a common intention in the starting point of all the works that will be exhibited, but I don’t think you will be able to see it at a glance. A significant difference between you and me is that your materials are always recognizable: resin, coloured pencil, paper tape; while mine – which I won’t list entirely – are synthetic and natural resins, various pigments and additives, constantly transforming and, therefore, “camouflaging”.

I’ll explain: by using a thick polymeric binder mixed with graphite, I can create, through a spatula, a surface similar to a mirror, or at the very least, a polished metal. Yet, the very same thing can be obtained through an emulsion of sandarac and mica – a mineral – rendered extremely liquid.That said, the variation in my work is extreme, and as a consequence, so is seriality. So, where do you find variation? More so, do you actively look for it? At which level?

E: I have always tried to have a prototype I could clone, a proper recipe. But in this case, I preserved the prototype without cloning it. I tried to create artworks very close to the prototype, but with new variations that could give a unique shape to the ones I already knew. I found variation in “not having defined a single possible sequence of possible operations”; in other words, the recipe differed for every painting. Are you more drawn to the sesame seeds or to seeking a material that could become a starry sky?

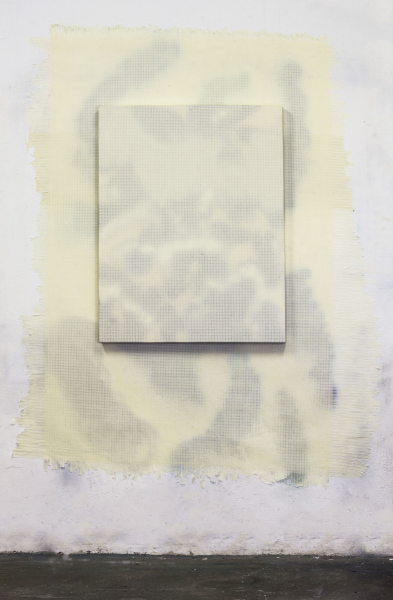

K: Have you ever gone to the supermarket, the butcher, or the greengrocer and bought something that attracted you even though you didn’t know how to use it? Or maybe you saw someone else using it, but you knew you would use it differently? Well. I am that person. I am attracted to the potential of different materials. The starry sky and the seeds are just a coincidence, and I want to keep training this dynamic because the materials I keep using in the same manner might have other “inclinations” to be discovered. I’ll make an example: a few weeks ago, I created a granulated colour with some pigments, a bit of glue, and colloidal silica.

I forced a dynamic that was supposed to bring me somewhere else, in the direction the material itself was suggesting. At that moment, it occurred to me that I once desired to create a stippled surface without painting the dots. And here we are. What is your relationship with your materials? The epoxy, for instance, is exceptionally rigid in every sense: you can’t miscalculate the doses, and it can’t be different from what it is.

I forced a dynamic that was supposed to bring me somewhere else, in the direction the material itself was suggesting. At that moment, it occurred to me that I once desired to create a stippled surface without painting the dots. And here we are. What is your relationship with your materials? The epoxy, for instance, is exceptionally rigid in every sense: you can’t miscalculate the doses, and it can’t be different from what it is.

E: No, you can’t make mistakes. Every mistake is irreversible; the resin encapsulates and blocks everything, it can fail to dry, become filamentous or sticky, but the worst happens when it catches fire. If I make a mistake, I have to throw everything away, which allows me to always be very focused and maintain a high attention threshold. I have developed, over the years, an aversion to objects, and I am trying to own less and less. By avoiding mistakes, I can create nothing in surplus.

K: Interesting! Obviously, I had never thought about it that way. Indeed, it might be frustrating for me to dwell on a less interesting work… I have never thought about having to throw something away, as, one way or another, anything goes with what I make. I have just put some leftover color (a mixture of I-don’t-know-what, I must admit) in a silicon ice cube mold. I don’t know if I’ll use it for something in particular, and if so, I don’t know when. In the meantime, it is left to dry there, and I will find a way to use it.

On the contrary, you say you have an aversion to objects. So, what is the bare minimum to create Erik’s works?

On the contrary, you say you have an aversion to objects. So, what is the bare minimum to create Erik’s works?

E: I think it’s the paper tape. And yours?

K: Have you ever created artworks using only paper tape? I wouldn’t know how to answer this question. All the materials I use are restrictions. I use the term “painting” as a convention, not to cross over to somewhat else or go too far. Anyway, I think I wouldn’t need anything; I would try to convince some professionals to use their skills to do something “improper” with regard to their order of ideas.

E: Yes, I have created some works using only some duct tape on a wall.

I should look for some pictures and send them to you. Which professionals would you choose? I’m curious.

K: As always, I wouldn’t look for long; I’d find something interesting around me. I’ve got a chemical engineer and a chef working on private jets. Ah, and then there is the god of water paint.

E: What would you like to do with this conversation? It is starting to take shape. Years ago, I read “Letters from Exile”, a collection of the correspondence between Josef Albers, who emigrated to America, and Wassily Kandinsky, who was living in Paris during World War II.

K: Ah, shoot, I thought you were going to ask me about the god of water paint…I don’t know what to do with this conversation yet, but I think its purpose will be clear soon enough.

E: I remember about the god of water paint and his advice. We talked about it when we painted the wall behind your studio. We should plan a day, or maybe two, to paint a wall together in Spring.

K: Absolutely! They are the only opportunities I have to paint vertically. It didn’t occur to me how destabilizing it would be. But, it was useful for one thing: I started using a sign apparatus on canvas again.

Click here to see Andrea Kvas and Erik Saglia show "SPAZIALE!" at the Gallery.